Vector-borne infectious diseases, such as malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, and plague, form a major part of the population affected by infectious diseases worldwide.

These diseases cause severe effects on the health, socio-economic status and development of an individual. Being a tropical country, Malaysia is highly prone to be affected by these vector-borne pathogenic diseases.

Vectors are the transmitters of disease-causing organisms, carrying them from the infected host to another uninfected guest. Vectors are usually arthropods, that may be contaminated with disease-causing pathogens which transmits the disease, or rodents, which carry the agent from a reservoir to a susceptible host. Vectors of human disease are typically species of mosquitoes and ticks that are able to transmit viruses, bacteria, or parasites to humans and other warm-blooded hosts.

Vector Control Measures

Infectious diseases transmitted by insects and other animal vectors have long been associated with significant human illness and death. Over the last few centuries, human morbidity and mortality due to vector-borne diseases have been on the rise and have exceeded that from all other causes combined. In the early 20th century it was discovered that mosquitoes transmitted diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, and dengue and this led to the use of pesticides, which helped to control these disease vectors. The adoption of vector control measures, including the application of a variety of environmental management tools and approaches, coupled with improvements in general hygiene, found some respite from major vector-borne diseases in the first half of the 20th century.

Today, vector-borne diseases are once again a worldwide concern and a significant cause of human morbidity and mortality. Malaria accounts for the most deaths by far of any human vector-borne disease. The causative agents, Plasmodium spp., currently infect approximately 300 million people and cause between 1 and 3 million deaths per year, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa. Dengue’s resurgence has been marked not only by epidemics, but also by the emergence of a more severe form of disease, dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF). Yellow fever, which along with dengue was controlled in the Americas by a variety of mosquito abatement techniques through the mid-20th century, remains a constant threat, with concerns that it might make its first appearance in Asia. Plague too seems to be making frequent guest appearances in various developing and under-developed countries, making it another pandemic threat.

In conjunction with World Malaria Day that falls on the 25th of April, we dwell more on this vector-borne disease that has been on the prowl for centuries.

What Is Malaria?

Malaria is a serious, sometimes fatal, disease that is caused by a parasitic infection of the red blood cells. There are 4 kinds of malaria parasite that can infect humans:

- Plasmodium falciparum, which is the most serious form of malaria, and can be life-threatening;

- Plasmodium vivax, which is less serious and not usually life-threatening;

- Plasmodium ovale, which is not usually life-threatening; and

- Plasmodium malariae, which is not usually life-threatening.

There have also been some human cases of malaria resulting from infection with Plasmodium knowlesi, a species that causes malaria among monkeys in South-East Asia.

What causes Malaria?

Malaria is contracted by the bite of mosquitoes. When an infected mosquito (the Anopheles mosquito) bites you, it injects the malaria parasites into your blood. These parasites then travel through the bloodstream to the liver where they multiply. During this time, when the parasites are in the liver, you will not feel ill. The parasites then eave the liver and enter the red blood cells where the parasites grow and then burst the red blood cells, allowing them to move to another blood cell. At this stage, the parasites release toxins into the bloodstream and you will begin to feel ill.

How Common Is Malaria?

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that each year, more than 200 million people are infected with malaria worldwide. Malaria is a common problem in areas of Asia, Africa and Central and South America. Unless precautions are taken, anyone living in or travelling to a country where malaria is present can contract the disease.

What Are The Symptoms Of Malaria?

What Are The Symptoms Of Malaria?

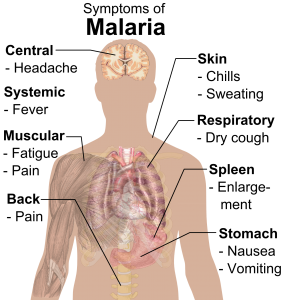

The symptoms of malaria consist of fever and flu-like illness, including shivering, chills, headache, muscle aches, tiredness and a general feeling of being unwell. Because the symptoms are so general, malaria is often misdiagnosed. Nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea may also be present.

Malaria can also cause anaemia and jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin) because of the damage to the red blood cells. If not promptly treated, the most serious form of malaria (Plasmodium falciparum) may cause kidney failure, seizures, mental confusion, coma and death. For most people the symptoms of malaria will begin 7 days to 4 weeks after the mosquito bite. However, the incubation period may be longer if you have taken an inadequate course of malaria prevention medicines.

Two kinds of malaria (Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale) can cause relapses and some parasites may remain dormant in the liver for up to 4 years after you have been bitten by a mosquito.

How is Malaria diagnosed?

Malaria is diagnosed by checking the blood for the malarial parasites (a pathological test). If you become ill with a fever or flu-like illness while travelling in high-risk areas and up to one year after returning home, you should immediately seek medical attention. You need to tell your doctor that you have been travelling in countries where malaria is a risk. While a single positive blood test result is proof you have malaria, a single negative test is insufficient to exclude it. If you or your doctor suspect that you have malaria, at least three negative blood tests can be required to make sure you don’t have malaria.

How is Malaria Treated?

Malaria is treated with certain types of prescription medicines. However, the type and length of treatment depends on which kind of malaria is diagnosed, where you were infected, how old you are, and how ill you were at the start of the treatment.

How is Malaria Prevented?

Before leaving for an area where malaria is a risk, visit your doctor to find out about antimalarial medicines. Normally, antimalarial medicines are taken for several days to a week before you travel and continued for one to 4 weeks after you return. The most active time for the mosquitoes that transmit malaria is from dusk till dawn and you should try to avoid going outside during this time, if possible, wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants in light colours when going outside after dusk.

Use mosquito repellents. However, do not apply these repellents on the hands of children who may wipe their hands on their eyes or put their hands in their mouths.

Sleep under a mosquito bed net that has been treated with permethrin insecticide if you are not staying in a screened or air-conditioned room. Use insect sprays in your living and sleeping areas. Lighting a mosquito coil can also be effective. It is still possible to get malaria even after using all the prevention measures, so if you experience any of the symptoms of malaria seek medical attention as soon as possible.

The Road Ahead in the Management of Vector-borne Diseases

While acknowledging the global burden of vector-borne diseases, as well as the daunting obstacles to much-needed research on their control, prevention, and treatment, there is a need of interdisciplinary collaboration and research between different medical and paramedical disciplines to look for opportunities and synergies. Like vector-borne diseases themselves, research in this area is rife with thorny problems, but also abundant with opportunity.

Abraham Mathew Saji

Abraham Mathew Saji

References:

1) WHO Malaria Factsheet; 19 Nov. 2018; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria; accessed February 22, 2019.

2) Peter Lam; What to know about Malaria; Medical News Today; 19 Nov. 2018; https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/150670.php; accessed February 22, 2019.

3) Yao H.L; Malaysia is ground zero for the next malaria menace; Science News; Vol. 194, No. 9, Nov.10 2018; pp. 22; https://www.sciencenews.org/article/malaysia-ground-zero-monkey-malaria-deforestation; accessed March 14, 2019.